In the early 2000s, it wasn’t easy being a fan of trash-horror movies from the outer limits. Admitting that you watched Las Vegas Bloodbath to a co-worker was like saying that your favorite pizza topping was kitten toes. For me, the stigma was so overpowering that Bleeding Skull! was launched anonymously in 2004. I was in a band at the time, and the consensus was that connecting my name with these movies might have a negative impact on our tiny fanbase.

A lot can happen in fifteen years.

Today, we’re living in a golden age of appreciation for trash-horror movies. No one has to feel like a subhuman for worshipping at the altar of Andy Milligan, Roberta Findlay, or Chester N. Turner. From gorgeous Blu-ray restorations of The Vineyard to bootleg YouTube uploads of Chainsaw Scumfuck, accessibility has led to acceptance. These films will always be subversive. But for those of us who appreciate teleporting to the magical netherworlds found in Bloody Muscle Bodybuilder in Hell and Where Evil Dwells, we never have to feel ashamed. These movies are our safe spaces. They help us process life, death, and reality — our lives are richer because of them. This realization is allowing me to see things in a whole new light.

In the book Film as a Subversive Art, Amos Vogul wrote, “The film experience is total, isolating, hallucinatory . . . a place of magic where psychological and environmental factors combine to create an openness to wonder and suggestion, an unlocking of the unconscious.” This sentiment is so beautiful that it almost makes me tear up. When we apply this mindset to movies that aren’t traditionally considered “art,” the lines blur. Who’s to say that the immersive dreaminess of Detour can’t be replicated in Sledgehammer? Why should there be a barricade between the overlapping textures of Last Year at Marienbad and Death Bed: The Bed That Eats? Art doesn’t have to conflict with trash. In fact, it’s more fun when they coexist — especially in a movie that was never intended to be anything more than a cash grab.

Satan’s Blade was shot around California’s Big Bear Lake in the early 1980s for the price of a decent motorhome. Writer-director L. Scott Castillo Jr. never made another movie that was released. In a 2014 interview, Castillo said: “I was designing it so that it would be cheap enough to actually make a motion picture. I chose to make a horror movie because it was the cheapest and easiest to do . . . and we’d all make money.”

“Satan’s Blade is one of my favorite slashers.”

— No one ever

Historically, this movie has been dismissed for its uneven pace, ragged production values, and sleepy performances. In my review for Bleeding Skull! A 1980s Trash-Horror Odyssey, I wrote: “The stark photography, wretched acting, and tedium erupt with a certain something . . . lovable, but not essential.”

After revisiting Satan’s Blade via Arrow Films’s Blu-ray, I can confirm that the writer of that review was a total asshole. When watched through the prism of this stunning restoration, the movie isn’t simply lovable or essential — it’s a work from beyond the veil of humankind, a true broadcast from the cosmos.

Satan’s Blade can best be described as Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes From a Marriage on an edible bender with Friday the 13th Part 2 in Andy Warhol’s jacuzzi. It could also be the real-life version of the movie-within-a-movie that John Travolta’s character is working on in Brian De Palma’s Blow Out.

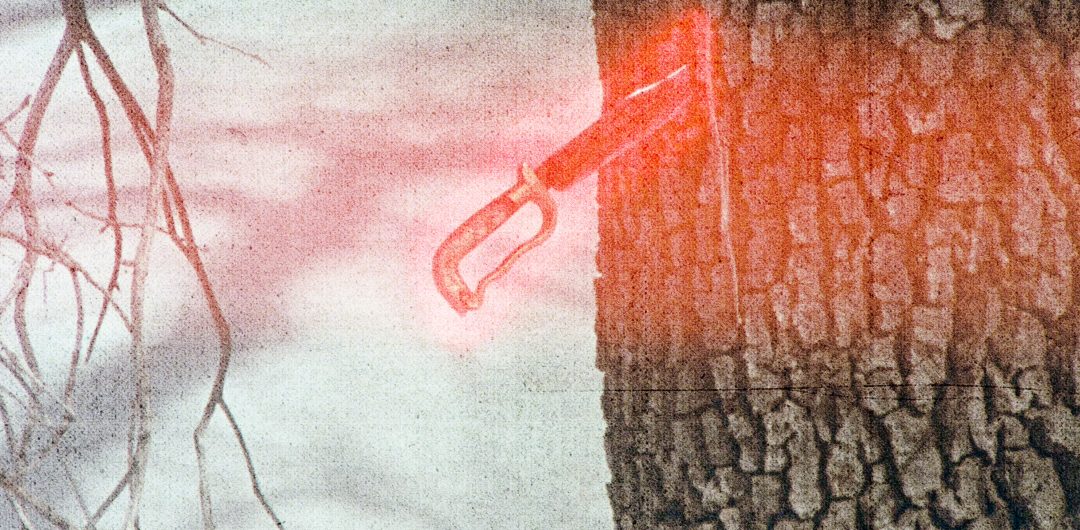

On the surface, Satan’s Blade follows a standard slasher template — party animals visit an isolated location in the middle of winter before facing death by an evil force wearing black leather gloves. But below the surface, there’s no handhold on reality. Satan’s Blade doesn’t deliver the coked-out splendor of Boardinghouse or Winterbeast; it’s more chill, kind of like what would happen if Runaway Nightmare went full slasher. So if you expect shredding guitars, consistent engagement, or lawnmower decapitations, stick with Sleepaway Camp III: Teenage Wasteland. But if you can appreciate a DIY slasher that materializes as an unintentional abstract art project, let’s blast off.

The movie opens with a sleazy bank robbery. The brief scene feels like it was recorded on a security camera during a heist by alt-Earth versions of Patty Hearst and the Symbionese Liberation Army. The robbers gun down the female tellers, but not before suggestively removing the buttons on their shirts with a knife. However, it’s revealed that the thieves were also women. This twist is obviously meant to be base-level exploitation from a dirty old dad’s perspective. But absorbed through 21st century goggles, the queer implications are fascinating. This is the first indication that the movie is being brought to us from . . . somewhere else.

From there, Satan’s Blade settles into 45 minutes of hangouts at a mountain resort with two married couples and some ladies on a college break. This is the point in the movie when most viewers check out. But don’t give in! Because this is where the extraterrestrial wavelength fully develops, as detached performances from a Warhol-ian soap opera collide with slasher tropes, arguing, and lots of fishing. Without this exposition, the eventual explosion of gritty violence wouldn’t have as much impact.

The resort has some history. As the story goes, Satan lives in a river by the property. He uses his blade to possess unsuspecting humans and spread death over the mountain. Satan’s pawns mark the walls of cottages with symbols drawn in blood. I love this detail, mostly because it aligns with the Satanic panic crisis of the early 1980s. But also because the characters in the movie have no reaction to the marks, like they’re staring at a plate of spaghetti instead of a death token soaked in human guts.

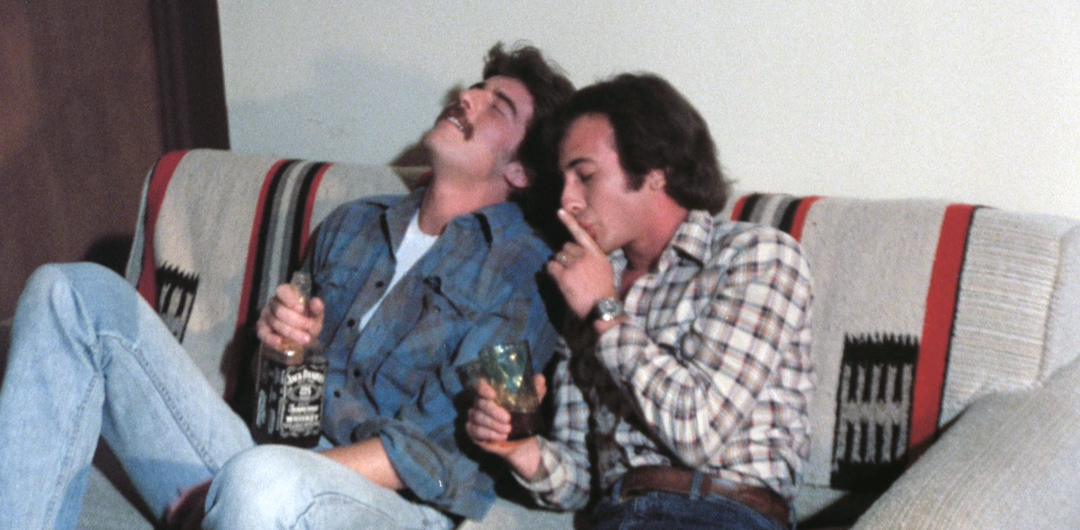

During the first night of their stay, the married couples pair off into rooms. The ladies want to “call it a night” and “turn in early.” They make no attempt to hide that they want to have sex with their husbands. If we were watching Madman or Home Sweet Home, that’s exactly what would happen. But this is Satan’s Blade. Instead of following their wives upstairs, Al and Tony stay on the couch and crack open a bottle of whiskey. They descend into a drunken stupor. The guys slap each other’s legs, shush each other by touching fingers to lips, and sit so close that you’ll want to yell “KISS HIM!!” at the screen. Like the reveal after the bank robbery, this lengthy scene raises some questions. Is this male bonding or a coded cry for freedom? The subtext probably wasn’t intentional, but it’s just one more notch on the surreal belt that grips tighter and tighter as we go.

Meanwhile, cops eat sandwiches. Al and Tony prank the ladies next door. One of the ladies has an incredible abstract nightmare about a killer who slaughters everyone in the house. There’s grocery shopping, woods exploration, and a chow-down of cold pizza. One couple questions their marriage, then have sex. The character of Lil — played by Janeen Lowe, a rare Asian American actor to have a lead role in a 1980s slasher — holds down the fort with advice and support when everyone starts losing their minds. The actors have a disinterested vibe, like they just took a handful of painkillers and are settling into a night of enchantment. But then, after all of the build-up, a frenzy of brutal killings is unleashed. The beige walls are soaked with bloodshed, screams, and gratuitous nudity. This is totally unexpected, and that’s why it’s also totally effective.

The aesthetic qualities of Satan’s Blade work in tandem with the content to establish a drugged-out mood. Twinkling pianos and droning synthesizers conjure a soundtrack from the basement lair of a Satanic cult. Crude photography perfectly aligns with the upside down universe that we’re stuck in, as do the gaudy plaid couches and flower-print curtains. Like Ghostkeeper and Iced, the winter setting provides psychological warmth in the form of Moon Boots, fireplaces, and snow drifts (not the kind you snort). Character names inexplicably change from Lisa to Doris, from Scott to Rich, and back again. The bow on top is a nihilistic ending that wouldn’t feel out of place in a late-1970s issue of Weird Vampire Tales from Eerie Publications.

Satan’s Blade seems to have happened by accident. It almost feels like performance art, a burlesque of a slasher made by art-fart college kids. The movie was never meant to be interpreted this way, and that’s exactly why I love it. You could say that I’m overthinking it, that this is simply a horror movie made by amateurs with a lack of resources. But if you say that, you are clearly a person who hates having fun. Personal interpretations breathe new life into neglected movies. Today, Satan’s Blade doesn’t belong to a cynical filmmaker or buttholes who live by the problematic “so bad, it’s good” credo. This movie belongs to me, you, and anyone else who cherishes it for what it is — a slime-covered diamond that shines through the void of vanilla sameness.

In an episode of the late-and-great Freaks and Geeks, the character of Nick Andopolis shares his philosophy on life:

“You need to find your reason for living. You gotta find your big, gigantic drumkit. You know?”

I do! With those wise words ringing in my head, I’m finally ready to say it:

Satan’s Blade is one of my favorite slashers.