Originally published in Bleeding Skull! A 1980s Trash-Horror Odyssey.

When people don’t show up for work in the United States, they get fired. No one is happy. When people don’t show up for work in Europe, they get Zombie Lake.

Everyone is happy.

In the right hands, unfortunate circumstances can lead to majestic work. Check out Doris Wishman’s A Night To Dismember for a taste. Like that accidental beauty, Zombie Lake is in the right hands. As the story (and Phil Hardy’s Overlook Encyclopedia Of Horror) goes, gutter-poet Jess Franco was all set to direct the film, which he also wrote. However, when the clapboards clapped, Franco was M.I.A. Eurocine put out a call. Jean Rollin answered.

Zombie Lake is magic. At face value, it’s a full frontal nudie-cutie that showcases a handful of placid WWII zombies. That’s reason enough to love it. And, if anyone other than Jean Rollin had directed, that might have been the only reason to love it. Like fellow Frenchman Eric Rohmer, Rollin is a man beset with cataloging his sexual obsessions on film. Over. And over. And over. But where Rohmer elegantly presents the exploration of men, women, and their sexual desires, Rollin pummels us with breasts, pubes, and their respective placement within the canon of horror. Rollin’s work is just as intriguing and meticulous as the more respected Rohmer, but it’s not for intellectuals. There’s nothing emotional about Rape Of The Vampire — it’s simply beautiful trash. So what happens when this assured artisan is thrown into a situation with no time to think, no clout to spread, and little room for craftsmanship? You got it: magic.

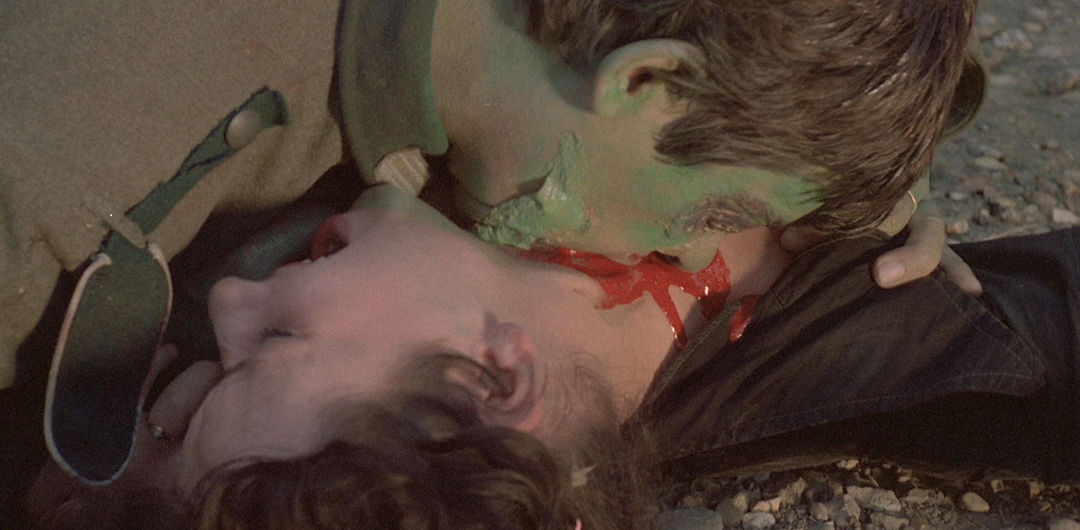

Slightly west of Ogroff‘s enchanted forest lies the Lake Of The Dead. It works on the same principle: whenever someone gets close (in this case, very naked ladies), they bite the big one at the hands and mouths of green-faced soldier zombies with bulging eyes. Sometimes, zombies emerge from the lake with not one drop of water on them. Other times, the lake magically transforms into a backyard swimming pool when the camera moves underwater. Soon enough, some hastily assembled villagers, led by lethargic mayor Howard Vernon, decide to take care of business. Flashbacks of sex during wartime reveal that the head zombie has a child; he wants to give her his dead wife’s pendant. Most of this happens after a Volkswagen full of female volleyball players arrives at the lake. There is also a giant flamethrower.

For 80 minutes, Zombie Lake floats by on a stoned cloud of adolescent escapism, melodramatic oafishness, and spontaneous technique. That is to say, it’s a sumptuous mess, residing on a tier where absurdity begets lo-fi grandeur. Everything about the film is wrong. Everything about the film is right. And, unlike a majority of Rollin’s filmography, you don’t have to work for it — the slow-burn dreaminess is innate. Everywhere. Ominous string quartets, haunting pianos, and cocktail hour jazz (all courtesy Daniel White, Jess Franco’s stock composer) complement the quivering camerawork while propelling the mood. Shots of equipment, crew members, and people cracking up were not edited out, giving the film a misplaced sense of real-life urgency. Boobs serve as padding when zombie soldiers do not. Everyone appearing onscreen appears to be either highly confused or highly disconnected or highly entertained. Just like us. And, probably, just like Jean Rollin.