In Laurel & Hardy’s Our Relations, Oliver Hardy says, “You can trust me insipidly.” It’s one of their most enduring puns and there’s a good reason why.

Ten minutes into The Grapes Of Death, the camera floats away and the gaze shifts. We’re no longer engaged with two women as they travel on an empty train. Rather, we’re engaged with the empty train itself. Minutes later, the camera completes its cold, gentle glide through the vacant cars. We arrive where we started. Two women on a train, chatting lightly about nothing at all, while noting that “No one but us would take a vacation in October.”

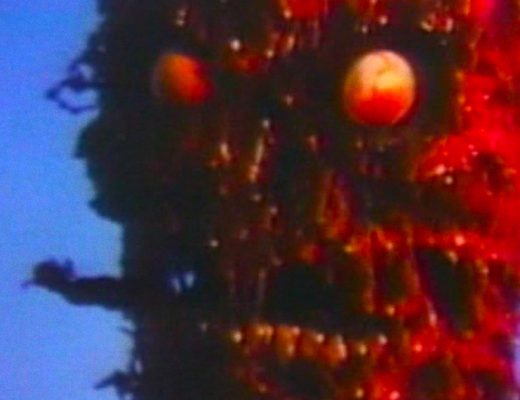

The train stops. A man boards. His face is melting. With total objectivity, he kills one of the women, then sits quietly as if nothing happened. And that’s when I thought of that pun from Our Relations.

The Grapes Of Death is not the most compelling film in Jean Rollin’s filmography. In fact, similarities with the earlier, more challenging The Nude Vampire run deep. This is a lushly decorated vista of negative space and fluttering humor. And while the artsy flamboyance of Nude has been replaced by a desire to simply gross us out, Rollin’s intent remains the same; we must trust him. Even when it seems we shouldn’t, we must. Implicitly. Or insipidly.

Elizabeth escapes from the train, screaming. She runs through fog, empty fields, and dilapidated church yards. A single arpeggiated synthesizer is her only companion. Seeking retreat inside a small home, Elizabeth finds the occupants suffering from the same malady as the man on the train. They have sores that melt. Sores that visually resemble a combination of Dijon mustard and Play-Doh. Sores that make them crazy. And so it goes.

Much like Agnes Varda’s Vagabond, Grapes strolls along in a very-straight, very-grim line. It’s one woman’s journey across an anxious landscape that she doesn’t understand. Only, Rollin’s concern with social relevance and emotional dry-heaves is transitory. Instead, he offers a Euro-trash variant on George Romero’s The Crazies — more eloquence, less headiness, and a focus on the gaps between.

Jean Rollin is a visual filmmaker. Slight moments of poetic insight, as in Fascination or The Iron Rose, are often disrupted by his overwhelming sense of design. But he never had much money. So when it becomes apparent that the emphasis in Grapes lies in pitchforks-through-breasts, faces-through-windshields, and severed head revelry, the trust is twofold. One, we must trust that Jean Rollin will provide us with a foothold in this cheap-yet-beautiful wasteland. Two, Jean Rollin must trust us to step into that foothold and never step out. It’s a lot to ask. But, like most enduring puns, the film’s title secures its worthiness.

As The Grapes Of Death moves, it grows. And with that growth comes understanding. This isn’t Jean Rollin’s most distinctive or engaging movie. It’s too lucid and slightly strained towards the end. But removed from that context, this is a quiet, unpredictable European gore film that benefits from Rollin’s preference for good design. You just have to trust him.