During the Rapture, some will be left behind and others will be swept up to meet the lord. Not everyone gets to go, so the lord will have to make some hard choices. Heaven has no space for the nonessential. Think of it this way: Earth is a giant house with plenty of closet space and heaven is an overpriced tiny studio in the East Village. Some shit just isn’t going to make the move. So this leads me to my next question: Will this movie make the move?

A pair of hands edit film the old-fashioned way, back when you glued strips together. All you decrepit old farts out there will know about this. The hands packs up a key, a canister of film, and a cassette and mails it to a man named Jose.

Meanwhile two filmmakers work on a scene where a buxom vampire emerges from a coffin. They break the scene down. They discuss how the actress is looking directly into the camera, a clue that tells the audience she is “enjoying being a vampire.” They discuss where they want the fade out to start and what it means. It is film studies circle jerk session, ham-fisted and bloated with pretension and self-importance.

Jose drives through the streets of Madrid, looking at different theater marquees and billboards: Superman, Phantasm, Oliver’s Story, The Deer Hunter, Bambi. The scene is set to a dramatic opera. As an audience, we are supposed to understand that this scene—and this movie—is an ode to the cinema. It is a film about Film. This scene is followed by the sound of me sighing.

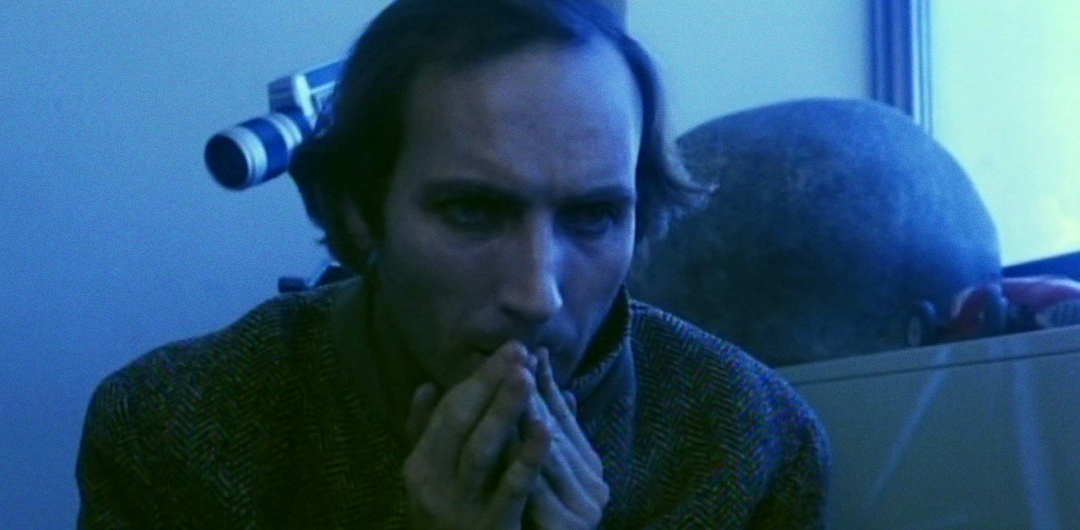

Jose comes home to find a woman in his bed and he’s pissed about it. So he shoots some smack, and like every movie that features smack, there’s a close-up of a syringe going into an arm. At some point Jose strips the girl naked because he’s cold and wants her robe. She does not wake up during this process. He watches the film and listens to the cassette that was mailed to him. There’s a gravelly loud whisper that goes on to narrate the entire movie. Narration is at best, a tool that pushes the plot and develops character, and at worst, it is a lazy convention that is endlessly grating. This is narration at its worst.

The film continues in flashbacks and present day, where Jose and a woman named Marta go out to her aunt’s country house and snort coke that was squirrelled away behind old picture frames. There’s a disheveled, tortured young filmmaker named Pedro who cries anxiously when people watch his films. He has a doll with light-up eyes that makes the TV go on the fritz. Pedro also watches Jose sleep. True story: My friend had a college roommate who’d watch her while she was sleeping. Julie would wake up in the middle of night to see her roommate sitting in a chair and staring at her. It’s actually creepier than it sounds. Pedro and Jose have some sexual tension and there’s a scene where they hang out in bed and play with goop. I don’t understand the significance. But I do understand that the men in this movie are uncircumcised. They are European, after all.

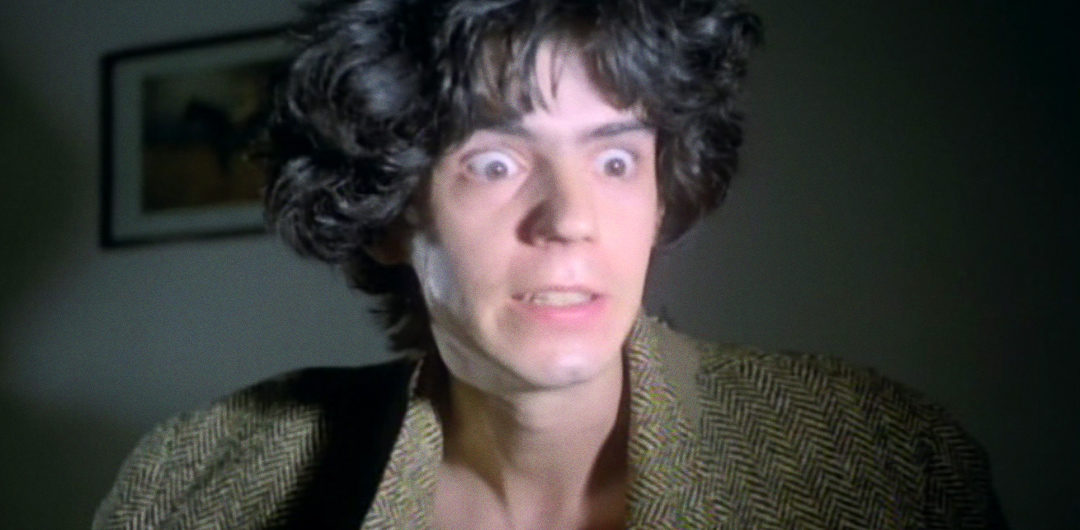

Jose and his friends do drugs, make films, do more drugs, and watch Pedro’s disjointed, experimental work. Interestingly, Pedro’s work is far more fascinating than the actual movie. His films are a collage of found footage: vintage vacation film from Venice, Italy and Disneyland, a bed of daisies, a pair of horses, the Taj Mahal, the Hollywood Walk of Fame, stock footage of Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco and the Mayan Pyramids in Mexico, and time-lapse footage of clouds and gardens. He explains that he tries “to film occult rhythms.” It’s reminiscent of Koyaanisqatsi (which came two years later). I could watch Pedro’s film all day. Truth be told, Arrebato should have just been Pedro’s work and not anything else.

After thirty-five minutes, the plot is opaque with no signs of it getting clearer. However, the heart of Arrebato‘s theme does come through. This is a film about the other type of rapture—the one where you are swept away by a passion. In this case, it’s the ecstatic state that comes from the power of film or love or lust or drugs; it’s a force that consumes your soul. And while I love the idea and sentiment behind the film, the execution falls short. The problem is that it’s boring. The narration is taxing. The plot is inscrutable. The characters aren’t compelling.

But despite all of this, Arrebato is magnetic.

Director Iván Zulueta does an expert job of building tension, even if it’s unclear what we are actually tense about. There’s a quiet, creepy mood and a consistent, low-level anxiety that permeates everything. There’s artful cinematography, a drug-addled trance that involves a Betty Boop doll, and a three-way in an elevator. At some point, Pedro explains he’s been making the same film for centuries. Centuries? There’s just enough suspense and confusion to keep the film going through the final sequence. While the film has a ton of ideas that don’t deliver, it’s still ambitious and mesmerizing in its own way. It also has another element that I love—a moment when a character actually says the theme of the entire movie:

“All my life, it was like a huge wank without cum.”