Let’s get negative.

The title track of The Velvet Underground’s White Light/White Heat LP kills me. It’s like a furious french kiss in broad daylight, sloppy and electrifying in its brevity and imperfect perfection. Then, “The Gift” kicks in, an eight-minute, slack-rock narrative which extols the merits of smart-ass nihilism. “The Gift” directly opposes “White Light.” It’s less pop, more cynically experimental, and not built to be appreciated on any sort of wider level. But I never skip it.

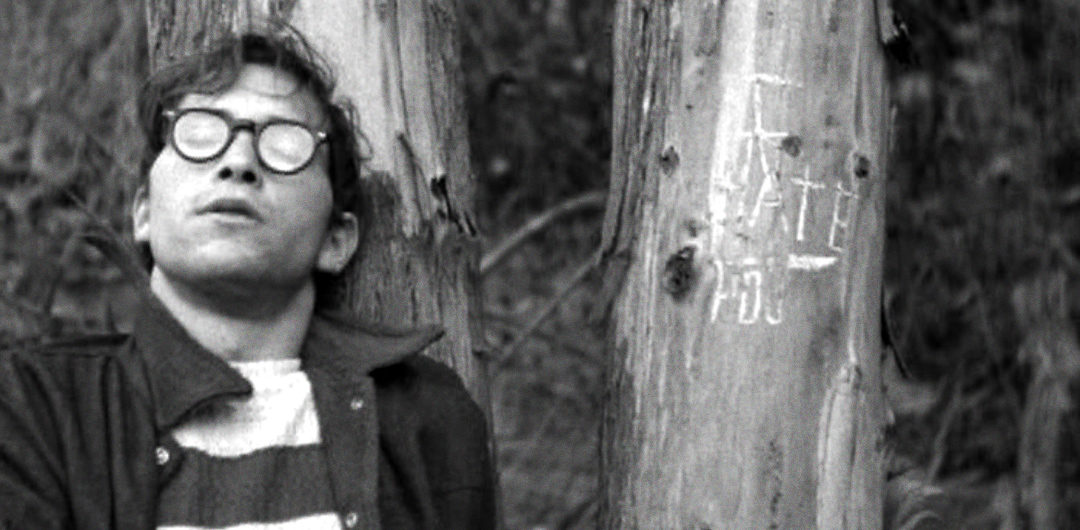

Nick Millard’s Oddo opens with a backwoods folk song and a collage of negative photography. There are jungles, bombs, knives, stabbings, slaughterhouse butcheries, and the pinning of medals to chests. Like most of his films, scant rationality commingles with a creative language that is only understood by Millard, and Millard alone. The opening of Oddo makes little sense. Sixty minutes later, the movie is over. And it still makes little sense. But one scene explains all. Toward the middle of the film, our protagonist carves something on a tree. He turns, faces the camera, points a gun to the sky, and reveals the carving:

“I HATE YOU”

Oddo isn’t as satisfying as Nick Millard’s “hits.” It lacks the frantic consistency of Criminally Insane and Satan’s Black Wedding and the inhuman madness of .357 Magnum and Death Nurse. Makes sense. This was 1967. Millard was just warming up. The leather shoe fetish is present and accounted for. The perpetual jump-cuts are not. But while Oddo may move slowly and establish an actual attention span, however arduous, the film’s culmination as a hazy, pessimistic anomaly makes me smile.

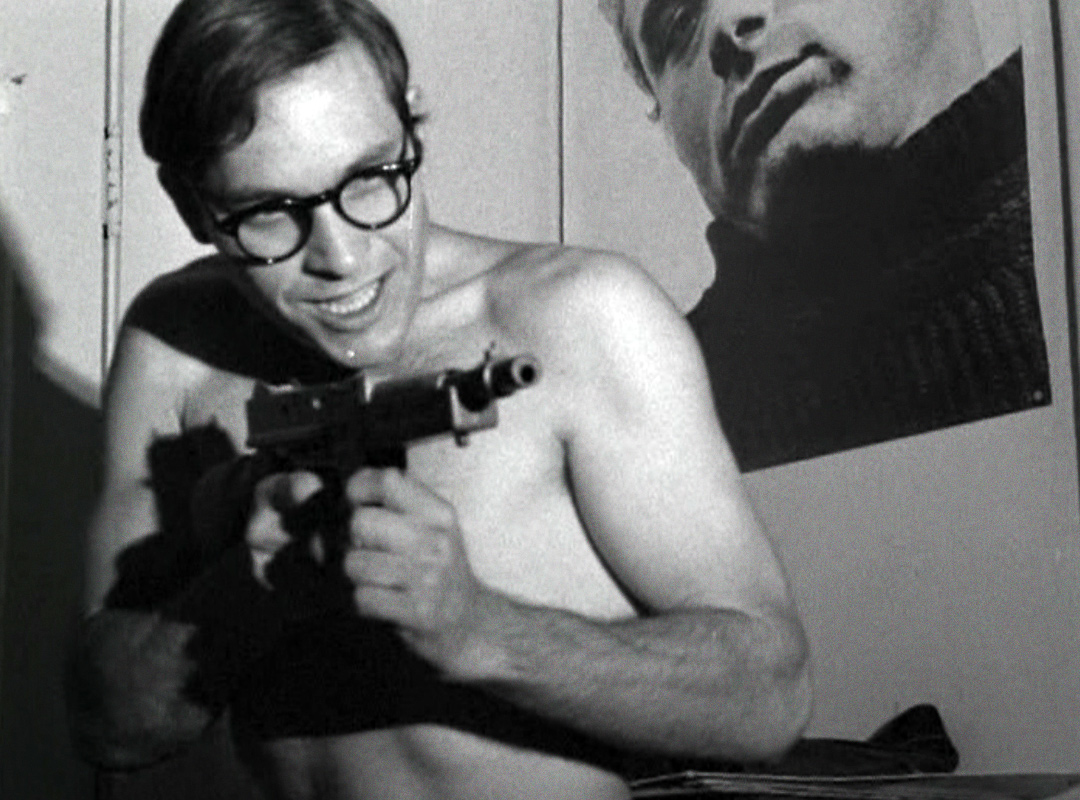

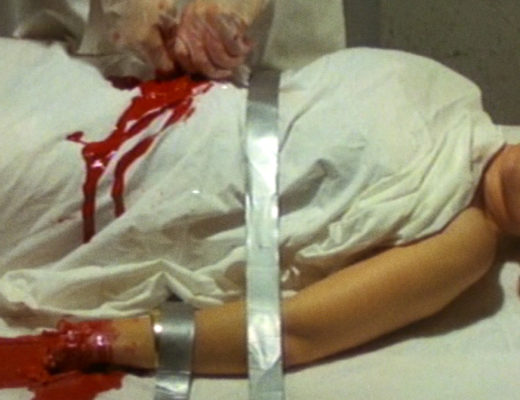

An unnamed psychopathic soldier returns to San Francisco from Vietnam, while a narrator, intoning much like John Cale on “The Gift,” shares a running stream-of-consciousness rant while the soldier does things. Like beating the shit out of hippies. And murdering his lesbian step-mother. And receiving a topless shoe-shine. There’s a lot of roaming, street typography, pop iconography, and inexhaustible semi-sex scenes which are really just women stripping and rubbing up against people, shoes, or mirrors. It’s all very distant and cloudy. The ending commences a trend of dejected, ‘Nam-vet angst that would continue on with stuff like My Friends Need Killing years later.

Removed from the context of Millard’s filmography, Oddo is an amusing project. In form, it’s like Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie floating by on a ten-dollar budget and an undergrad’s dream. In content, it’s not much of anything. Messages are muddled, sex is evaded, and violence is dull. Lulls hold precedence over peaks. Despite the beautiful handheld photography and righteously discordant soundtrack, this is Nick Millard filling up space. Of course, the same can be said about Death Nurse. But Death Nurse coerces boredom into a cunning muse. You never know what’s coming next, and what comes next is often so strange that it feels profane. Therein lies the thrill. Oddo isn’t as mythical or staggering. But it’s still a notable experiment in underground negativity, working for Millard in much the same way that “The Gift” worked for The Velvet Underground.

And that’s why I’d never skip it.