Sixty minutes into Wendigo, two men paddle down a river in a canoe. This is not surprising. Because up until this point, most of the movie is made up of people paddling in canoes. One guy says:

“To tell you the truth, I’m really glad to be getting off like this. Just man and nature alone in the wilderness. Paddling, back-packing, sleeping on the ground. Really roughin’ it.”

Accent on the “rough.”

Six people travel to a remote island in a helicopter and talk about how they’re going to land the helicopter. Then they land. A French man, called “The Frenchman,” is not French. He sounds like Will Ferrell impersonating Pepé Le Pew impersonating Al Pacino. The only woman on the trip is the girlfriend of one of the guys. She flirts with everyone, strips naked behind a horse, and eventually has sex on the ground with the group’s Native American guide, Billy. Speaking of Billy, he keeps warning the group about the curse of the Wendigo. In a flashback that is play-acted by the Frenchman, we learn that the curse of the Wendigo is based on a man who was burned alive by some thieves. We see endless, pitch-black shots of nature. We see endless, pitch-black shots of people talking at camp sites. Eventually, two people explode because that’s what the Wendigo does to assholes who trespass on his land. But before that happens, the Wendigo appears aka the camera zooms at trees.

Lots of no-budget exploitation movies center around the mundane. Some of these movies use the concept of non-happenings to their advantage. In Runaway Nightmare, two bug farmers stumble on a gang of female freedom fighters who are at war with the mafia — in theory. In reality, Runaway Nightmare is about people hanging out in a house. But the mannerisms of the cast and the details that the filmmakers choose to share with us are so disconnected from reality that an uncharted subset of limbo materializes. That makes the movie engaging. Doctor Strain The Body Snatcher is another example. In that movie, a scientist discovers the secret to soul transference and creates an army of zombies. But not really. Because he’s too busy walking in hallways, staring at candles, and standing in a field. The sloppy, collage-like Super 8 construction of Doctor Strain makes watching it feel like we’re walking through a living dream. That singularity is what makes the movie special.

Wendigo also focuses on things that don’t happen. But it’s not like Runaway Nightmare or Doctor Strain. No risks are taken. It doesn’t feel passionate — it feels like an obligation. This is a workmanlike soap opera that revolves around a camping trip. Unfortunately, it’s presented as an exploitation-horror movie, due to tacked-on flashbacks about a beastly myth. What this means is that Wendigo is a static movie about people getting on horses, walking on trails, and, of course, paddling in canoes. There were two minutes in this seventy-four minute movie when I was not consumed with violently agonizing boredom.

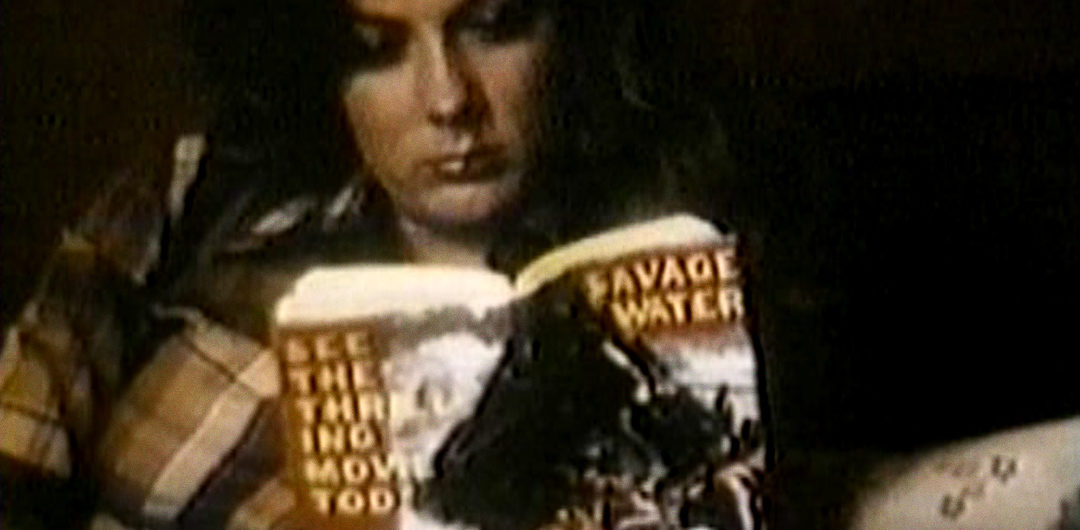

Director-writer-producer Paul Kener is also responsible for Savage Water. Like Wendigo, Savage Water is a soap opera that revolves around a camping trip. But instead of a mythical monster, the pretense comes in the form of a “slasher.” Basically, Kener made the same movie twice in a row. He was clearly ambitious. Anyone who makes a movie is ambitious. But Kener’s movies lack that sliver of social courtesy, the insight that filmmakers need in order for their work to communicate successfully with other humans. Wendigo and Savage Water both feel like they were made by someone who had never seen a movie. But instead of that lack-of-awareness morphing into other-worldly triumph, as it does in Another Son Of Sam, we’re just left feeling empty and frustrated.

This movie might have been more tolerable if there was a Wendigo in it.