Most people believe that the sci-fi genre peaked with movies like 2001, Star Wars, and The Matrix.

Those people are wrong.

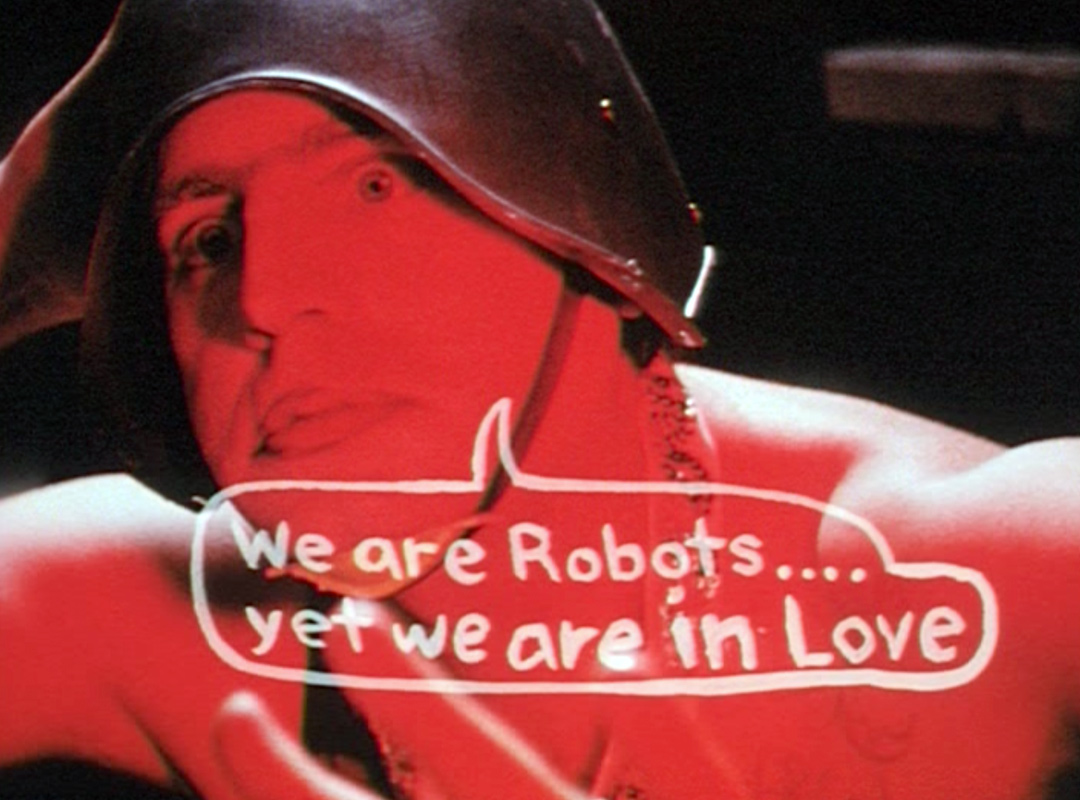

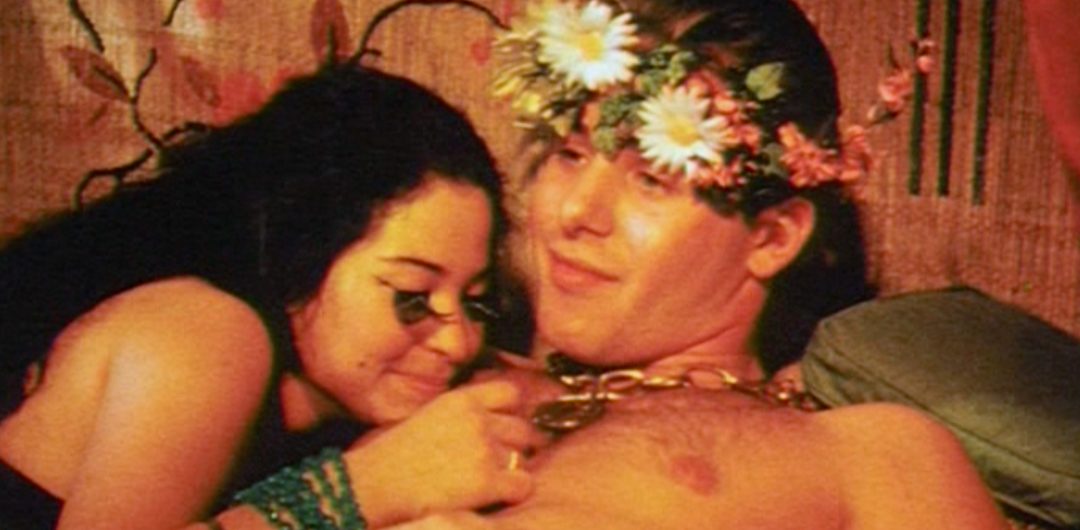

It’s one-hundred years in the future. Humans obsess over Fleshapoids, which are mechanical robot people who obey their every command. War and weapons are extinct, so the Fleshapoids are tasked with more important work — like pouring bowls of plastic fruit on their human masters and massaging hunks who wear tiny sarongs. But one day, the impossible happens. A Fleshapoid named Xar falls in love with another robot named Melenka. This sets off a chain of events that finds Prince Gianbeno (George Kuchar) and Princess Vivianna (Donna Kerness) embroiled in face-slaps, a switchblade murder, and the most adorable robot birthing scene that you’ll ever see.

In my review of Mike and George Kuchar’s Born of the Wind, I shared why their massive DIY filmography is so important to underground film history; why their work remains a beacon of sparkling light in a flat world, embracing sexuality and ignoring traditional filmmaking. So instead of repeating myself, you and I are taking the hallucinogenic pill known as Sins of the Fleshapoids — Mike Kuchar’s most ambitious and beloved film — and blasting off this planet for 43 minutes of pulsating, over-saturated joy. Don’t forget the glitter.

Watching Sins of the Fleshapoids evokes the same emotions as eating raw cookie dough or receiving a surprise postcard from someone you love. It just feels good. Shot on 16mm in a cramped apartment and furnished by the neighborhood thrift store, the movie is a raw summation of every aesthetic touchpoint that compelled the Kuchar brothers to do what they do. From the pitch-shifted orchestral LPs on the soundtrack to the crude background paintings, from the male-on-male gaze to the comic book word balloons that appear onscreen, Sins presents a wild, duct-tape fueled unreality that feels like Pee-Wee’s Playhouse for mid-century crackpot adults. Or a silent film from another dimension where live sound was never invented. Whatever way you interpret it, there’s no denying the movie’s impact. When the fidgety narrator exclaims, “How could two robots feel affection for one another? It’s against nature, against the laws of the universe,” it’s clear that Kuchar is working with bigger themes of acceptance. This adds an extra layer of emotional depth, a welcome complement to the candy-colored dreamspace.

Speaking of which, let’s talk about color.

In a 1967 issue of Film Culture, Mike Kuchar said, “My specific aim was to bombard and engulf the screen with vivid and voluptuous colors. Because Sins is a fantasy of science-fiction . . . I boosted the colors according to its category: fantastic and unreal.”

Mission accomplished. Filtering the Technicolor visions of Douglas Sirk through the no-budget urgency of an Andy Milligan movie, Sins is flooded with reds, greens, blues, oranges, and any other color you’d find in the literal crayon box that was used to create the movie’s opening titles. This use of color pushes Sins to another level. If the movie was filmed in black and white, the impact wouldn’t be the same. The fact that Kuchar had the foresight to pair the subject matter with the ideal form of visual communication proves that he was never just a guy with a camera — he’s an artist. One that I’m grateful exists.

Deep down, we’re all Fleshapoids. How we deal with that knowledge, and how we let it affect those around us, is what defines our lives. That said, one of the best ways to provide self-care for yourself in a post-2020 world is to watch a movie with the names Mike or George Kuchar on it. The narrator’s final line says it all:

“Where the humans failed to find love, the machines have succeeded.”