Frank Harris’ My Life And Loves was published in 1925. Mr. Harris was famous because he had famous friends, and also because My Life was a 1000 page memoir about having tons of sex that probably didn’t happen.

Titus Moede released The Last Of The American Hoboes sometime in the late 1960s. It’s a half-documentary, half-god-knows-what with fake beards, collage-like visuals, and triple flashbacks-within-flashbacks. Like the life and loves of Frank Harris, Hoboes is a compelling for both its self-contained scope and its questionable authenticity. Did Britt, Iowa’s National Hobo Convention really exist? Can bedbugs provoke men to kill other men? Are snowflakes made from notebook paper? Outlaw Motorcycles may clue us in.

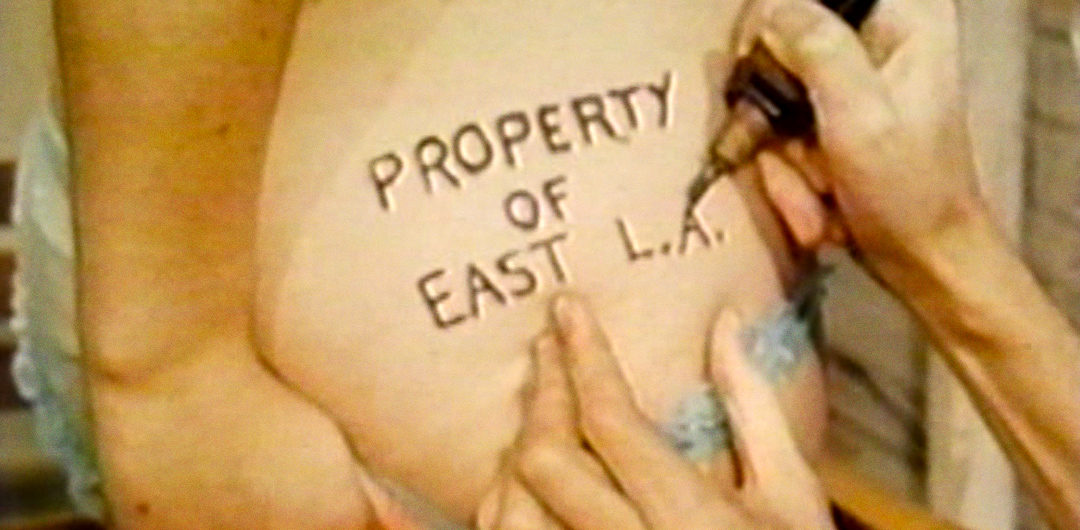

If The Last Of The American Hoboes is Titus Moede’s 1000 page epic, then the earlier Outlaw Motorcycles is his 100 page walk around the block. Outwardly, this 30 minute observation on California biker culture feels empty — there’s little emotion to glean. It’s simply a series of narrated montages documenting several biker clubs over the course of a weekend. There are run-ins with cops, TV news crews, and surfer kids. We hang out at a Hollywood hot dog stand called The Yankee Poodle. People dance. There’s a curbside wedding. Nipples are tattooed, and a funeral unfolds. Then, the film promptly ends, hinting at something more, yet never quite getting there. Until you watch it again.

Titus Moede was not a member of a biker gang which donated canned goods to charity. That happens in this film, but clearly, it wasn’t happening in real life. That’s the difference between Outlaw and Hoboes — we can tell what’s authentic and what isn’t. There’s not much mystery. But, there is a vulnerability in contrasting mistaken edits, broom closet dubbing, and poorly composed reenactments with documentary footage. It’s as if T.M. was saying, “This is what I want to do and this is the way I want it to be. Plus, I want to share it with you. So don’t laugh.” As strange as it sounds, Outlaw Motorcycles feels intimate. Moede has invested himself fully in order to please himself. It’s personal filmmaking with no intimation of loftier goals.

That’s why this film gets better with multiple viewings. The Ed Ruscha-styled signage helps, as does a distant glimpse of the in-progress Watts riots. But those things are captivating on their own, through the lens of any camera. Here, it’s the fact that Moede’s sincerity is running the show, presenting another half-documentary, half-god-knows-what with lots of surface-level appeal, but little commercial pull. We know what we’re watching and why it was made. We know which bikers are real and which are not. And, we know that snowflakes can be made out of notebook paper, as long as Titus Moede believes it.