Q: Why do winos house their booze bottles in brown paper bags?

A: Because they don’t want to see the end coming.

That pretty much says it all.

Prior to a thirty year shuffle down the thoroughfare of Pornville, USA, late actor-writer-director Titus Moede aka Titus Moody was part of Hollywood’s weirdo-fringe elite. He starred in Coleman Francis’s The Skydivers. He was a jack-of-all-trades for Ray Dennis Steckler. He also had something to do with James Bryan’s elusive (and filthy) The Dirtiest Game. Given this beautiful resume, is it any surprise that Moede would eventually concoct a remarkably strange film of his own? Of course not. Furthermore, is it any surprise that said film would turn out to be…incredible? You bet.

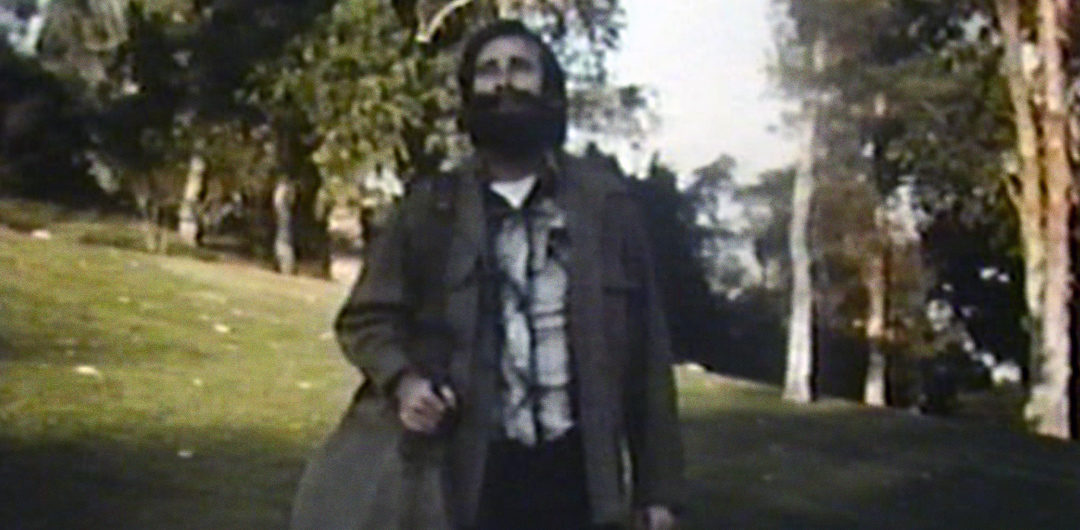

Bid hello to the The Last of the American Hoboes. It’s a half-documentary, half-god-knows-what that delves into the sad, challenging, and ultimately inspiring plight of the American hobo circa 1967. In the hands of docu-artisans such as Frederick Wiseman or Albert Maysles, the concept of Hoboes may have matured into something else entirely. But this is Titus Moede, director of Love Sandwich. Therefore, we get a sincere, somewhat affecting mélange of triple flashbacks, schizo edits, gutter folk-pop, and phenomenal fake beards.

At 50 minutes, I figured out what was going on. As a man (Titus with a “beard”) and his grandfather walk along a dusty country road, Gramps relates the story of his Hobo Summer, in which he travelled cross-country to Britt, Iowa’s National Hobo Convention. Of course, this leaves the door wide open for a free-associative anti-narrative on all things hobo. As flashbacks give way to flashbacks that give way to more flashbacks, Moede assembles a ragged, non-stop deluge of footage — some authentic, but most so awkwardly fictionalized that it feels sublime. We learn the difference between a hobo (“Nice and warm…not materialistic.”) and a bum (“They steal, kill, do anything!”). We experience what it’s like to ride the rails, fend off flophouse bedbugs, and live in spooky caves. We understand that a life of hobo-ing may lead to a life in silent motion pictures. Soon, the Britt convention arrives. And it’s awesome. Handheld footage of the parade, the King & Queen coronation, the eating of Hobo stew, the carnival, and the Hobo Band Jam (they play saws, shovels, and broken harmonicas) lead us to a gloriously fitting sunset.

The intent behind Hoboes will forever baffle. At all times, the film says everything. And nothing. There is death. Sadness. Hilarity. Optimism. Survival. Tedium. And yet, a purpose remains decidedly elusive. Or does it?

Titus Moede was clearly passionate about his subject matter. So much so that he threw craft out the window and did the best he could with the resources at hand. Accordingly, the aspirations of Hoboes are found not in its literal presentation, but in its D.I.Y. ethos. Don’t get me wrong — the film’s odd post-dubbing, non-acting, and impromptu philosophies do much to bolster its attraction. But in adhering to his singular vision, no matter how skewed or resource-deficient, Moede crafted a fascinating ode to an American folk lifestyle which will never exist again. Both in-front-of and behind his camera.

Pass the brown paper bag.