In 1992, I watched Nirvana smash their instruments on Saturday Night Live. My dad was in the room. When the commercial hit, he looked at me, laughed, and said, “Just like Pete Townsend used to do. I take back what I said about Kurt Cobain — he’s alright.”

Ten minutes into Murder In A Blue World, a vaguely futuristic family watches a television set. A still shot of Stanley Kubrick appears on the screen. An announcer says, “Now, we present Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. This is a symphony on the theme of violence.” Then, a gang of black-leather dissidents, somewhat reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s Vinyl (itself an “interpretation” of Anthony Burgess’ original novel), break in and enact their own variation on the home invasion sequence from A Clockwork Orange. Later, Sue Lyon, star of both this film and Kubrick’s Lolita, is shown reading a copy of Nabakov’s “Lolita”. All of this made me smile.

Murder In A Blue World aka Clockwork Terror is an unexceptional Spanish exploitation film. Or, it would be an unexceptional Spanish exploitation film, if not for the meta-enhanced pilfering. And that’s the whole point. While beautifully designed and crammed with creativity, Murder is like a Jose Larraz film without the explicit sleaze — good-looking, but empty. Yet, the Clockwork Orange associations can’t be ignored. They caress your elbow, tug your ear, and gently whisper, “You will accept this film. Because it is reminding you of something that made you feel good, and when you remember that something, it makes you feel good again.” It’s a smart move. It’s also an easy move. Fanfare, controversy, hopeful promises — that’s what exploitation is all about. And whether you smash a guitar on national television or literally borrow someone else’s film to embolden your own, second-generation embezzlement works. My dad is living proof. And so am I.

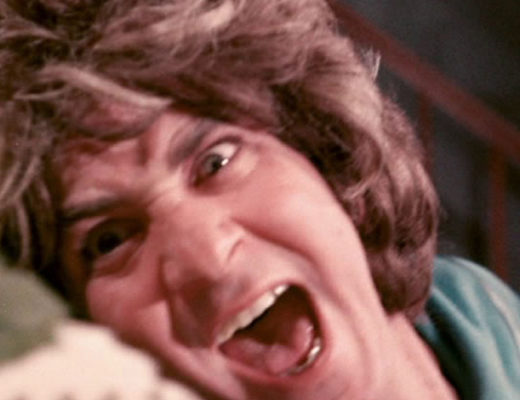

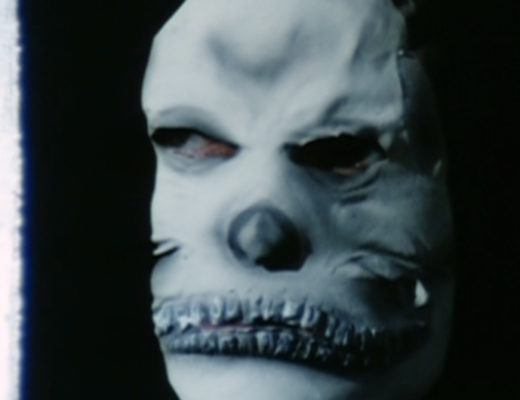

Surprise! This film has a plot. No surprise! I’m not going to share it with you. Because, believe it or not, the movie thrives on unexpectedness. So just know this: there’s a gang. They wear red motorcycle helmets, the previously mentioned leather suits, wield whips, and drive around in a little dune buggy. Sue Lyon is a nurse at a hospital, and she’s involved in experiments on juvenile delinquents. There’s also a sex-killer, frequent homosexual under-and-overtones, and statements on media and technology which feel like haggard refugees from William Klein’s The Model Couple. The ending rules. The melodramatic love tangent (“I want to get to know you…profoundly.”) does not.

Underneath the novelty, Murder is an exercise in design. That’s fine by me. But it runs way too long. For all of the amazing moments when strange camera positions, Serge Gainsbourg-esque orchestral swoops, and pop-art incidentals coalesce in artsy splendor, there’s still a shortage of resource. Ideas are constantly flying at us, but the script, actors, and 100 minute length can’t handle them. So this stylized sci-fi crime thriller quietly buckles under the weight. And unlike Killer’s Moon, another Droog adherent, there’s no juicy tastelessness to liven up the limitations. Sexuality is tepid. Violence is mostly unseen. An opportunity almost feels lost.

Murder In A Blue World isn’t A Clockwork Orange with a fourth of the budget and even less potency. Rather, it’s the dream that Kubrick’s film might incite in your subconsciousness. Everything’s a bit warped, a bit different, not exactly how you remember it. Tangents and free association take hold over actualities. That’s what makes this film so fascinating — just the fact that it exists, that someone had the guts to produce and release it so quickly after A Clockwork Orange, and do so with such poise. As a narrative, Murder is a padded-out bore. But as a conversation piece, it’s a bizarre pop-culture paradox that incites you to watch. And then watch again.