This is an updated version of a review that was originally published in Bleeding Skull! A 1990s Trash-Horror Odyssey.

Everything is better in Mexico, including Child’s Play.

Tony and Annie are happily married and living in New York City. Tragedy strikes in Mexico when Tony’s aunt passes away while clutching her most prized possession—a horrifying clown doll that comes to life as a 400-year-old little person who is dressed as a horrifying clown doll.

Tony and Annie inherit his aunt’s mansion, money, and clown. They move to Mexico City. Tony looks for a job. Annie cleans the house. They have sex in the dark. For real. Because the screen is pitch black while they do it. The next day, Tony returns home and says, “I got a job!” Annie says, “Surprise! I’m having a baby!” This would be great news except for the fact that Annie finds the clown doll and says, “It has an evil face,” and then the clown gets revenge by pushing her down the stairs. Annie dies, but the baby lives. That’s just one more reason not to have children.

Tony names the kid Baby Roy, just like Dr. Steve Brule’s son in Check It Out! with Dr. Steve Brule. Baby Roy magically turns 10 years old in the span of fifteen seconds and finds the clown doll in the attic. Baby Roy says things like, “My little clown is waiting only for me,” and, “My little clown must be tired.” Tony marries his secretary, the clown makes out with Tony’s secretary, and congratulations to the human race because Herencia Diabólica is the best drug that money can buy.

In 1965, filmmaker Alfredo Salazar unleashed the horror-western hallucinogen known as The Rider of the Skull. No one talks about this movie, but everyone should. The Rider of the Skull feels like it escaped from an alternate dimension where Dracula is president, every day is Halloween, and pulp crime magazines are substituted for newspapers. It has a werewolf! A vampire! A headless horseman! And a masked cowboy, dressed in black and sworn to protect the world from skull-faced cult members, cackling witches, and a dismembered head in a box! Salazar would go on to write some of El Santo’s wildest adventures (Santo & Blue Demon vs. Dracula & the Wolfman) and produce Night of the Bloody Apes, which is the finest movie about a psycho-sexually deviant gorilla that you’ll ever see. Obviously, Salazar was no stranger when it came to audacity and imagination. But it would be over two decades before he funneled this aesthetic into his ultimate trash-sludge masterpiece.

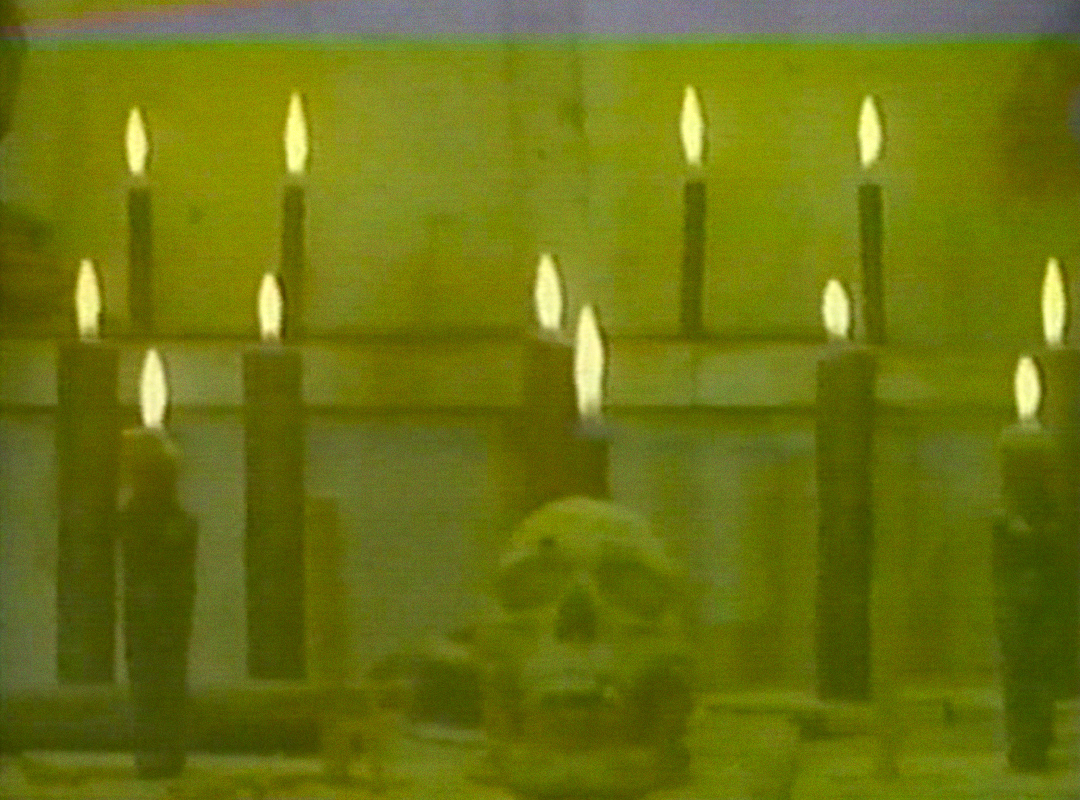

Herencia Diabólica blatantly steals the template of Child’s Play and adds endless scenes of padding and music that sounds like Soul Asylum conducting a circus orchestra with Yamaha keyboards instead of real instruments. No passion or thoughtfulness went into the planning or execution of this movie. The smeary 16mm photography captures important moments from behind office chairs and under bushes. Scenes of people being chased while walking last for 10 minutes with no resolution. Salazar is more concerned with filming a display in a park that features King Kong than the actors themselves. For these reasons and thousands of others, Herencia Diabólica can never be recommended to anyone who enjoys watching movies. However, these are also the reasons why I’ve watched it five times but still haven’t seen Lawrence of Arabia.

The secret weapon of no-budget DIY filmmaking is freedom. Because when a filmmaker has freedom, there are no boundaries on their creativity. In the wrong hands, a lack of rules can lead to Nightmare Asylum or Evil Sister—empty movies with little imagination that deliver nothing. But with Herencia Diabólica, freedom enables a mystical, galaxy-slaying combination of psychotic visuals that I will cherish until the planet explodes. I accept the fact that the majority of this movie’s runtime is less entertaining than watching a stranger mop their kitchen. But the rest of Herencia Diabólica—including the part where the clown throws someone off a roof and they turn into an even less convincing dummy than the one from the Ferris wheel scene in Nightmare City—offers me an experience that exists nowhere else. At least until I get dementia on my 90th birthday.

In the last scene of Herencia Diabólica, Tony, Baby Roy, and the clown doll board a plane. The camera slowly zooms in on the doll’s face, which comes to life and smiles. Baby Roy looks at Tony and says, “My little clown is very happy today, Daddy.”

I can relate.