Someone went on vacation and brought us a souvenir called Flesh Freaks.

FLESH FREAKS!!!

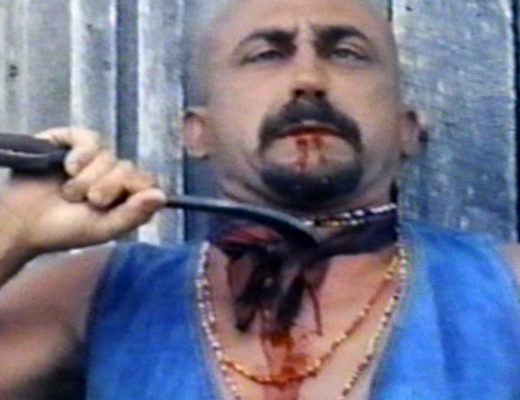

College students Barry and Stan have a lot on their minds. Barry has just returned to Toronto from an archeological expedition in Belize. Stan has a soul patch that would make Fred Durst blush. Stan is also trying to help his pal overcome a mysterious trauma (“You can’t bury your problems away behind walls of psychological barriers!”). Meanwhile, a beastioid that stowed away in Barry’s backpack is on the hunt for human bodies to possess. This probably has something to do with the desecration of sacred grounds in Belize, and the subsequent attacks by a mummy-zombie with a machete. Soon enough, Barry and Stan’s school is besieged by zombies who wear Dockers and stonewash denim. In a refreshing turn of events, it’s not the dudes who take control, make a stand, and save the day. It’s Jane — an African-American woman with a predilection for nail gun massacres.

Like Doug Barry with Blood Lake and John Polonia with Nightmare Vacation, eighteen-year-old filmmaker Conall Pendergast knew that good things happen when you incorporate real-life footage from your bitchin’ vacation into your homemade splatter-fest. In this case, Pendergast visited Belize and shot footage without knowing where it would end up. Eventually, he combined his home movies with trippy experimental collages, existential teen angst, and scenes of zombie violence involving a portable desktop fan. Then he came up with the greatest title for a motion picture after Violent Shit and Satan War:

FLESH FREAKS!!!

By the early 2000s, eight out of every ten shot-on-video (SOV) horror movies most likely featured a character named Dr. Romero — or Dr. Hooper or Dr. Carpenter — who developed flesh-eating mushrooms that fart. And that’s a shame. Because nothing kills a party faster than false sincerity. Flesh Freaks is an anomaly in the early 2000s SOV wasteland. This is a serious, energetic horror movie made on a micro budget by people who weren’t old enough to buy a six pack of Moosehead Lager. Pendergast admittedly wasn’t quite sure of what he was doing. But his bizarro instincts were unique enough to set the movie apart.

Visually, we’re treated to an onslaught of digital zooms, jump cuts, oversaturated neon, random cross dissolves, duotone tinting, and photography that never sits still. The last fifteen minutes of the movie erupt with slime, rubber monster masks, and geysers of fake blood. This isn’t a mindless excuse to show fists being punched through intestines, like Zombie Bloodbath. Similar to Tim Ritter’s Truth or Dare, Pendergast was a teenager who delivered a movie with grown-up emotions, situations, and practical effects that belied his age. And it almost worked.

Flesh Freaks features lengthy scenes of people walking down hallways, more footage of lizards, chimps, dogs, beetles, fish, and birds per minute than The Prey, and a relentless “cymbal ding” on the soundtrack that legitimately made me break out into an aggro-sweat. There’s also a prologue that gets repeated halfway through the movie. What I’m saying is that there isn’t enough substance here to sustain an 80-minute movie. But that’s okay. I may have been restless while watching, but I never stopped smiling.

At one point, Barry and Stan enter a theater to watch The Brainiac, which happens to be the most deranged and exhilarating Mexican horror movie on the planet. These kids had good taste, and Flesh Freaks proves it.