I’ve been immersed in Wendy Carlos’s Switched On Bach for the past three weeks. With each listen, I get further away from understanding how someone could actualize a work that defies explanation. All I’m left with is a sense of awe and disbelief.

Of course, the cheap Dixieland jazz, big boobs, and a cow sleeping in a hammock from Who Wants to Kill Jessie? are far cries from baroque, multi-tracked Moog synthesizers. Or are they?

Who Wants to Kill Jessie? deserves to have fifteen exclamation points after its title. Part of the eclectic and vitalizing Czechoslovak New Wave, the film excels at duality. On one hand, it’s a work of visual and comedic art. On the other, it’s a sub-Playboy fantasy. Put both hands together and you get Kryptonite for critics. So where does that leave us? Awe. Disbelief. And Jessie. And a roomful of beer.

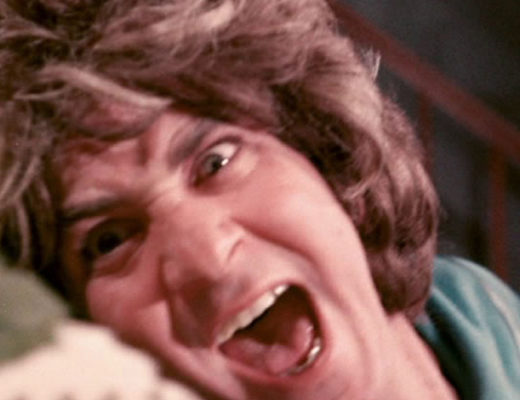

Professor Henry is stuck in a rut. Seeking escape from his routine marriage to fellow scientist Rose, Hank finds himself transfixed by the comic book “Who Wants to Kill Jessie?” The comic features the exploits of the sexy, Bill Ward-esque title character, who invents anti-gravity gloves while evading the clutches of villains Pistolnik (a cowboy) and Superman (duh). Naturally, Rose has invented a machine which can monitor dreams. Subsequently, she has also invented a substance which enables dreams to enter reality. A cow dreams of serenity. A man dreams of beer. Henry dreams of — wake up, Henry! Your subconscious is literally calling.

Who Wants to Kill Jessie? is an astonishing film to witness. It’s like a head-on, mid-60s collision between William Klein’s Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? and Harvey Kurtzman’s fledging magazine HELP!, though far more discerning (and fun) than either of those experiments. It’s shot well. The sets are stylish. It runs 80 nimble minutes. There’s the foundation. Now, the exceptions.

As you’ve most likely gathered, Henry’s dreams breathe life into the “Who Wants to Kill Jessie?” comic book. Therefore, Jessie, Superman, Pistolnik, and the anti-gravity gloves are unleashed upon the world. And the results are wonderful. Communication is achieved through ambient noises and on-screen word balloons, complete with beautiful 1960s typography. Visual effects, such as Superman’s feats of destruction and flight, are crude, yet apropos. Characters in the film address the comic book absurdities as if they were everyday occurrences, enabling the subtle comedic elements to breathe, rather than suffocate. Throw in some bubbling sexuality and unhinged action and you arrive at a movie which is much more “experience” than “film.”

That is to say, watching Jessie is like listening to Switched On Bach. You know not where it came from, or how its creation was even possible, but it exists. And that’s enough.