Fantasies can get you into trouble. But what’s trouble in the face of some vampiric menstruation?

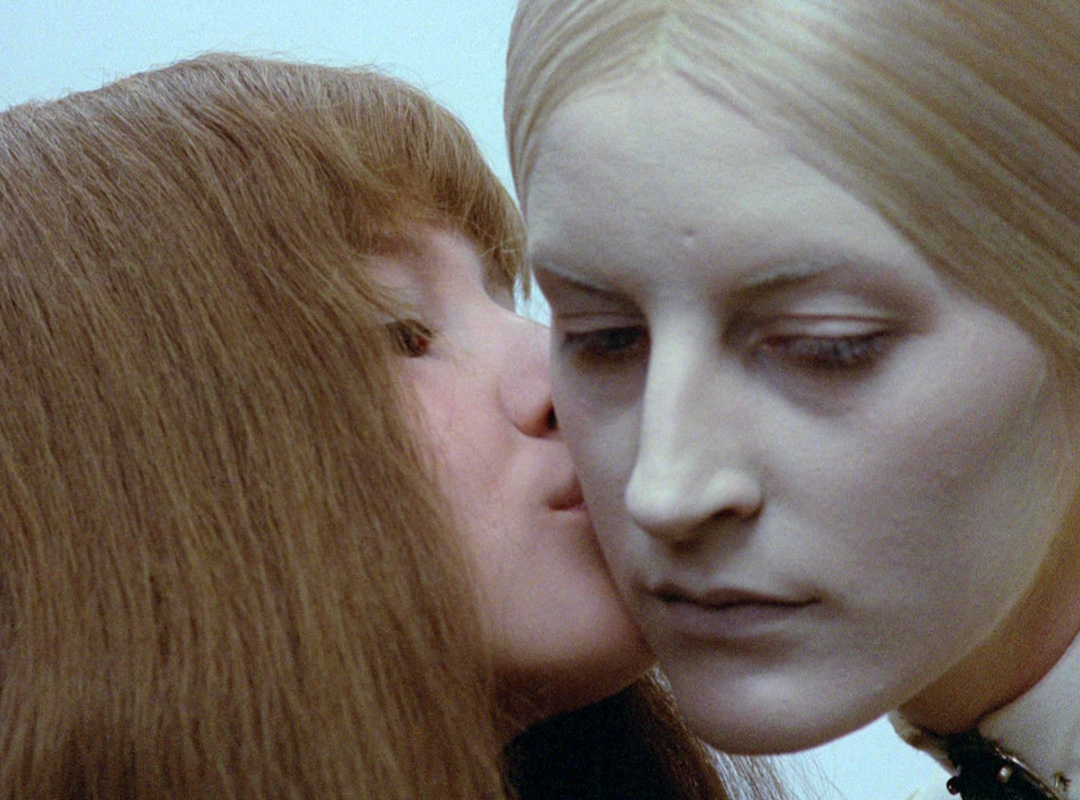

Valerie And Her Week Of Wonders has a lot going on. At its base, the film plies in dualism, which is not uncommon when we’re sniffing around the varied Czechoslovak New Wave. First, there’s 13-year-old Valerie and her budding sexuality. Second, there’s a family of vampires. On their own, either one of these concepts could carry a single film. But of course, these twains shall meet. And when they do, Valerie gets stuffed to the brim with questions, ghoulishness, and disarmament. Most of it visual. Some of it emotional. I could spend hours trying analyze and explain the gush of sexual and religious abstraction that flew around during this movie. But that doesn’t interest me.

Pop-cultural convergence is a wonderful thing. I mean, Jean-Luc Godard pretty much forged a career out of it. And why not? The idea of disparate elements finding themselves crammed together within one piece of work is invigorating. Especially in a format as comprehensive as film. It’s hearing trails of Os Mutantes in Headless Eyes. Sensing the hand of Claes Oldenburg in Mr. Freedom. In lieu of recognizable real-world parallels, this is what Valerie offers. You don’t watch it to gain some sort of insight into pubescent angst ala Murmur Of The Heart. You watch it because for 74 minutes, nearly every other scene will remind you of something that you enjoy about the state of unorthodox feature films circa 1970, almost as if your mind were a psychosomatic editor. That’s where the fun lies. Still, it’s not all heavenly voices and phantasmagoric landscapes. Teen angst runs deep.

One day, while floating over a daffodil patch with her magic earrings, Valerie discovers her first period.

And that’s all I know for sure.

From there, Valerie And Her Week Of Wonders assembles its own hazy reality. And it doesn’t care whether we grasp that reality or not. Valerie lives with her grandmother, who also turns out to be her cousin, who also turns out to be a vampire. Valerie is in love with a stable boy, who may be her brother. Valerie’s father is either a grotesque, demonic vampire or a nice guy with a beard. The village priest is into molesting. There are sexual encounters that end badly, lots of cobwebs, talk of cannibal adventures, several unrelated asides, and a witch burning. Through it all, a sole fact anchors: whatever this is, it’s Valerie’s happening — an unsettling, non-fairy tale fantasy that jabs. Sticks. And, of course, bleeds.

I’ll remember the strange and suggestive Valerie for many things. A determined sense of design. The lovely photography. Lubos Fiser’s enveloping score. The surprising subject matter. But most of all, I’ll remember how much it made me want to watch Who Wants To Kill Jessie? or Alabama’s Ghost or A Clockwork Orange again. Fantasy isn’t so troublesome after all.