Halfway through Twilight Syndrome: Deadly Theme Park, I shuddered. The movie reminded me of a recurring nightmare I have when I get overwhelmed. In the dream, I’ve parked my car in an unfamiliar city and I’m unable to find it. I walk and walk and search and search. But I can’t find the car. The situation is out of my control; it’s my subconscious massaging the real-life anxiety.

This is a low-budget video game adaptation about a clown who murders teens with balloon eggs that giggle like babies. The fact that it gave me the same haunting vibe as a literal nightmare says less about the effectiveness of the premise and more about the effectiveness of filmmaker Mari Asato. And what it says is that she’s a final boss who can’t be beat.

Five video game champions have been summoned to a mysterious amusement park. Greeted by a host who acts like a coked-out, dollar store mutation of Krusty the Clown and Pee-Wee Herman, the teens are presented with a game: Complete physical challenges and collect hidden Game Boy cartridges to advance to the next round. Or die! Each challenge leads the players to encounter an ever-escalating onslaught of surreal threats, including killer eggs that are the size of a Prius, possessed crossbows, and haunted rubber hoses that fill people with water and make them burst like in a Looney Tunes cartoon.

So far, the tone is light-hearted and fun—even when a girl gets lit on fire. But then the sun goes down. The abandoned park becomes a host for dozens of demonic clowns who don’t care about Game Boys or high scores. They just want to kill.

I don’t care if Twilight Syndrome: Deadly Theme Park isn’t as slick as Fatal Frame, Mari Asato’s later and more triumphant adaptation of a different video game. I also don’t care if this movie isn’t as savage as The Boy From Hell, her shot-on-video debut. What I do care about is the way that Asato works within her limitations to create hallucinogenic micro-movies that are filled with imagination, style, and heart. Twilight Syndrome is no different.

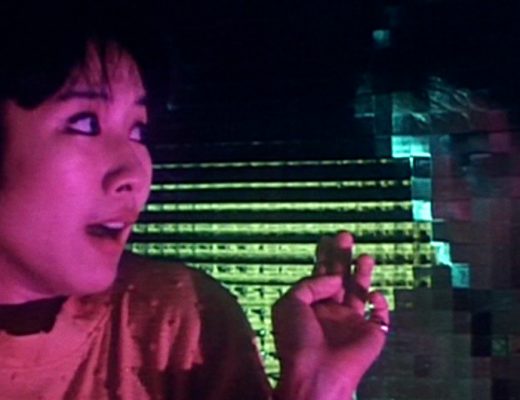

Although the movie looks like it’s held together—and sometimes not held together—by duct tape, Asato doesn’t let a choppy script or inconsistent pacing impact her confidence. She’s all in. You can see it in the unreal green screen effects (face explosions, cosmic black holes, landscapes rendered by a pointillism filter in MS Paint). You can feel it when the movie shifts from daylight to moonlight, and the hellish clowns appear. Just like real-life nightmares, the characters are faced with a distressing situation that they can’t control. There’s no escape. The fact that Asato enables us to relate to those feelings with such limited resources is a true accomplishment. I mean, I’ve watched Tokyo Gore Police twice. I’ll probably watch it again. But like most horror movies from the Japanese underground, Tokyo is more concerned with outrageousness than sentiment. When I watch that movie, I don’t empathize with Eihi Shiina after she slices a guy’s dick off. Maybe if Asato had directed it, I would.

At one point in Twilight Syndrome, a character clenches her fists, stares at the ground, and says, “It’s okay, this is not reality.” This is basically the same thing that I tell myself when I wake up from my car dreams.

Mari Asato wins.