In Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculin Féminin, a character explains why he had sex with his cousin at a funeral. It wasn’t a form of rebellion or an act of love. It was to “prove to ourselves that we were alive, that we existed.” While Godard’s presentation of this idea was completely stupid, his sentiment was not. No one needs to commit incest at a funeral to prove that they exist. But once in awhile, everyone needs some affirmation. And that’s what Cuadecuc, Vampir provides.

On paper, Pere Portabella’s Cuadecuc is an experimental documentary about the making of the late Jess Franco’s Count Dracula. But in reality, it’s an alternate version of Count Dracula, one with meta-enhanced imagery, synthesizers that sound like airplane engines, and smeary, 16mm black and white photography that looks like a third generation photocopy come to life. Count Dracula wasn’t Franco’s most “legitimate” movie just because it starred Christopher Lee as Dracula — it also scaled back the director’s eccentricities. There were no strip clubs, lesbians, or pubic hairs. There were no children being run over by cars. And so, Count became a straightforward horror film from an idiosyncratic and talented filmmaker. It was serviceable and atmospheric, but there was no electricity.

Cuadecuc is nothing but electricity.

This movie feels like an episode of Dark Shadows that was directed by Czech New Waver Václav Vorlícek after watching Carl Dryer’s Vampyr fifteen times in a row. Mostly silent, it literally follows Count Dracula chronologically, telling the same story on the same sets with the same actors. But between plot points that we can only infer, Cuadecuc cuts loose from its narrative. We see crew members spraying fake cobwebs on doors. Christopher Lee gives the camera a raspberry before getting into a coffin. Someone climbs out of a window, and from behind, we see that the window is built out of plywood and two-by-fours. Franco regular Soledad Miranda applies her make-up and smiles. Easy listening orchestral pop songs are cut in half by ambient noises, silence, or someone punching a piece of wood. Construction noises, like the ones from Godard’s 2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her, are heard as a bat flies on a wire. Crescendos build, end, then build again. Vampire women attack a man and the camera pulls back. The crew looks pleased.

After awhile, I stopped questioning what all of this meant and accepted the movie for what it was. Cuadecuc isn’t an allegory for the stresses of filmmaking, politics, or anything else that would require us to think. It doesn’t work like the similar Demon Lover Diary, which was a peephole into the damaged psyches of everyone involved in the making of The Devil Master. This is simply a beautiful, intoxicating mood piece. And it’s so simplistic that the mood dominates, like the mood in any Charlton comic book with the word “ghost” in the title. This thing is thick with dimestore gothic atmosphere — vampire fangs, graveyards, fake fog, flowing gowns, wooden stakes. Count Dracula had all of that, too. But Count Dracula didn’t feel like this. It didn’t have the power to immerse you in a calming vortex of anti-reality. This movie’s success lies in its singularity. It doesn’t really have a direct reference point. Rather, Cuadecuc feels like a culmination of everything that was in Jess Franco’s head when he made a movie (love, solitude, visual communication), but he didn’t direct this one. It’s a movie ABOUT him, not by him. And that makes it even more special.

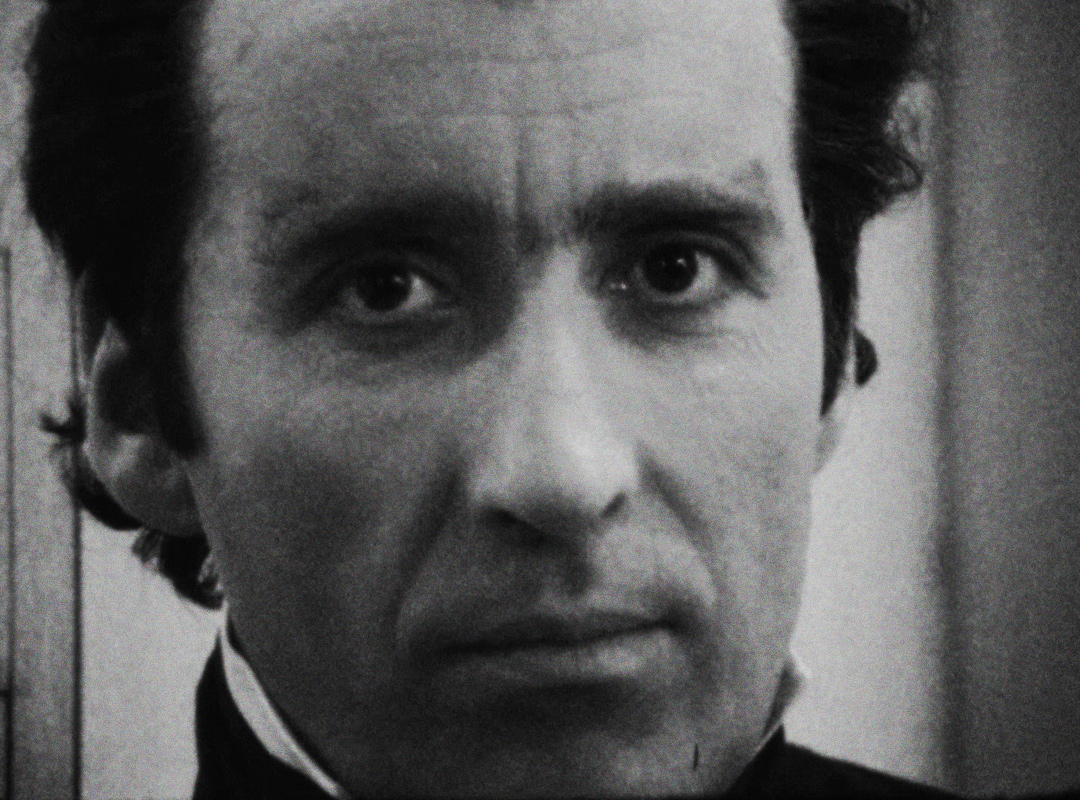

Cuadecuc ends with Christopher Lee reading a passage from Bram Stoker’s Dracula. It’s the part that describes Dracula’s death. When he’s finished, Lee closes the book and stares into the camera. The camera zooms in on his face. Someone yells “Cut!” and the screen goes black. This was the only scene in the movie that had synchronized sound.

If that’s supposed to mean something, I’ll let someone else figure it out.